Thursday August 24, 2017

I have been working on assessing Social Protection mechanisms in Somalia for more than a year where we are trying to understand the country’s social protection landscape.

In 2011, some 260,000 people died from famine. Given that 51.8 percentage of the population is poor with average daily consumption below $1.9 and 9 percent are internally displaced, it is only fair to despair over Somalia’s development, or lack thereof.

There is no denying that the country has suffered major losses due to climatic shocks as well as the civil war that had a huge impact on its social, economic and financial well-being. Other factors that have contributed to conflict and fragility are strong clan identities and land. Conversely, strong clan identities have also helped people survive famine and conflict.

But does that tell the complete story? Somalis have remained resilient in the face of these shocks. So, as development practitioners, we should try to look for missing pieces of this puzzle before designing any intervention.

Despite the impression that Somalia may be in dire straits, the traditional structures and other coping mechanisms have protected Somalis against these continuous shocks.There is no denying that the country has suffered major losses due to climatic shocks as well as the civil war that had a huge impact on its social, economic and financial well-being. Other factors that have contributed to conflict and fragility are strong clan identities and land. Conversely, strong clan identities have also helped people survive famine and conflict.

But does that tell the complete story? Somalis have remained resilient in the face of these shocks. So, as development practitioners, we should try to look for missing pieces of this puzzle before designing any intervention.

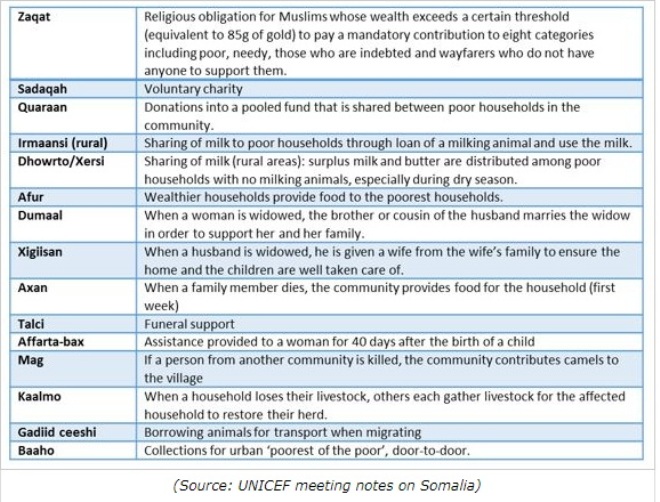

There is a heavy emphasis on helping the poor and vulnerable, albeit along clan lines. Table 1 gives a snapshot of prevalent traditional safety nets -- social programs that provide cash in exchange for children going to school or regular health check-ups -- that are integral to Somali’s society. Other development actors are also implementing various small-scale programs to provide social protection.

Table 1: Traditional Cash and In-Kind Safety Nets

Table 1: Traditional Cash and In-Kind Safety Nets

In addition to these forms of safety net, the mobile nature of Somali population has served as a coping mechanism where migration for better livelihood opportunities is a common phenomenon. Roughly 34 percent of the surveyed adult population (aged>15) have changed their dwellings over their lifetime.

Moreover, Somalis have traditionally engaged in pastoralism: a form of livestock production in which subsistence herding is the primary economic activity relying on the movement of herds and people. These pastoralists have adopted a nomadic lifestyle that relies on mobility to respond to the unpredictable supply of resources in the arid environment. And their livestock also provides them with a reliable source of nutrition not available without cash to others.

Lastly, remittances sent by the Somali diaspora have served as an important life line in which almost 21 percent of households received remittances in 2016. The total remittances sent back accounted for 23 percent of GDP in 2015, amounting to $1.4 billion.

Such huge receipt of remittances has been made possible by mobile money transfer initiatives like Dahabshiil and high rates of cell phone penetration (Figure 1). It has established the technological infrastructure that helped reach people even in remote areas, providing a secure medium for monetary transactions.

Moreover, Somalis have traditionally engaged in pastoralism: a form of livestock production in which subsistence herding is the primary economic activity relying on the movement of herds and people. These pastoralists have adopted a nomadic lifestyle that relies on mobility to respond to the unpredictable supply of resources in the arid environment. And their livestock also provides them with a reliable source of nutrition not available without cash to others.

Lastly, remittances sent by the Somali diaspora have served as an important life line in which almost 21 percent of households received remittances in 2016. The total remittances sent back accounted for 23 percent of GDP in 2015, amounting to $1.4 billion.

Such huge receipt of remittances has been made possible by mobile money transfer initiatives like Dahabshiil and high rates of cell phone penetration (Figure 1). It has established the technological infrastructure that helped reach people even in remote areas, providing a secure medium for monetary transactions.

No comments:

Post a Comment